PressureDependMultiYield Material: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 368: | Line 368: | ||

Code Developed by: <span style="color:blue"> UC San Diego (Dr. Zhaohui Yang)</span>: | Code Developed by: <span style="color:blue"> UC San Diego (Dr. Zhaohui Yang)</span>: | ||

---- | |||

References: | |||

# “Numerical Analysis of Seismically Induced Deformations In Saturated Granular Soil Strata,” (1994), Ahmed M. Ragheb, PhD Thesis, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY. | |||

# “Identification and Modeling of Earthquake Ground Response,” (1995), A. -W. Elgamal, M. Zeghal, and E. Parra, First International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, IS-TOKYO’95, Vol. 3, 1369-1406, Ishihara, K., Ed., Balkema, Tokyo, Japan, Nov. 14-16. (Invited Theme Lecture). | |||

# “Prediction of Seismically-Induced Lateral Deformation During Soil Liquefaction,” (1995), T. Abdoun and A. -W. Elgamal, Eleventh African Regional Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, International Society for Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, Dec. 11-15. | |||

# “Liquefaction of Reclaimed Island in Kobe, Japan,” (1996), A. -W. Elgamal, M. Zeghal, and E. Parra, Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 122, No. 1, 39-49, January. | |||

# “Analyses and Modeling of Site Liquefaction Using Centrifuge Tests,” (1996), E. Parra, K. Adalier, A. -W. Elgamal, M. Zeghal, and A. Ragheb, Eleventh World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Acapulco, Mexico, June 23-28. | |||

# “Numerical Modeling of Liquefaction and Lateral Ground Deformation Including Cyclic Mobility and Dilation Response in Soil Systems,” (1996), Ender Parra, PhD Thesis, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY. | |||

# “Identification and Modeling of Earthquake Ground Response II: Site Liquefaction,” (1996), M. Zeghal, A. -W. Elgamal, and E. Parra, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Vol. 15, 523-547, Elsevier Science Ltd. | |||

# “Soil Dilation and Shear Deformations During Liquefaction,” (1998a), A.-W. Elgamal, R. Dobry, E. Parra, and Z. Yang, , Proc. 4th Intl. Conf. on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering, S. Prakash, Ed., St. Louis, MO, March 8-15, pp1238-1259. | |||

# “Liquefaction Constitutive Model,” (1998b), A.-W. Elgamal, E. Parra, Z. Yang, R. Dobry and M. Zeghal, Proc. Intl. Workshop on The Physics and Mechanics of Soil Liquefaction, Lade, P., Ed., Sept. 10-11, Baltimore, MD, Balkema. | |||

# “Modeling of Liquefaction-Induced Shear Deformations,” (1999), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang, E. Parra and R. Dobry, Second International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 21-25 June, Balkema. | |||

# “Numerical Modeling of Earthquake Site Response Including Dilation and Liquefaction,” (2000), Zhaohui Yang, PhD Thesis, Dept. of Civil Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, Columbia University, NY, New York. | |||

# “Dynamic Soil Properties, Seismic Downhole Arrays and Applications in Practice,” (2001), A.-W. Elgamal, T. Lai, Z. Yang and L. He, 4th International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics, S. Prakash, Ed., San Diego, California, USA, March 26-31. | |||

# “Computational Modeling of Cyclic Mobility and Post-Liquefaction Site Response,” (2002), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang and E. Parra, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 22(4), 259-271. | |||

# “Influence of Permeability on Liquefaction-Induced Shear Deformation,” (2002), Z. Yang and A. Elgamal, J. Engineering Mechanics, ASCE, 128(7), 720-729. | |||

# “Numerical Analysis of Embankment Foundation Liquefaction Countermeasures,” (2002), A. Elgamal, E. Parra, Z. Yang, and K. Adalier, J. Earthquake Engineering, 6(4), 447-471. | |||

# “Modeling of Cyclic Mobility in Saturated Cohesionless Soils,” (2003), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang, E. Parra and A. Ragheb, Int. J. Plasticity, 19, (6), 883-905. | |||

# “Application of unconstrained optimization and sensitivity analysis to calibration of a soil constitutive model ,” (2003), Z. Yang and A. Elgamal, Int. J for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics, 27 (15), 1255-1316. | |||

# “Computational Model for Cyclic Mobility and Associated Shear Deformation,” (2003), Z. Yang, A. Elgamal and E. Parra, J. Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, ASCE, 129(12), 1119-1127. | |||

# “A Web-based Platform for Live Internet Computation of Seismic Ground Response,” (2004), Z. Yang, J. Lu, and A. Elgamal, Advances in Engineering Software, 35, 249-259. | |||

# “Earth Dams on Liquefiable Foundation: Numerical Prediction of Centrifuge Experiments,” (2004), Z. Yang, A. Elgamal, K. Adalier, and M. Sharp, J. Engineering Mechanics, ASCE, 130(10), 1168-1176. | |||

# “Dynamic Response of Saturated Dense Sand in Laminated Centrifuge Container,” (2005), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang, T. Lai, B.L. Kutter, and D. Wilson, J. Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, ASCE, 131(5), 598-609. | |||

# “Modeling Soil Liquefaction Hazards for Performance-Based Earthquake Engineering,” (2001), “S. Kramer, and A. Elgamal, Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research (PEER) Center Report No. 2001/13, Berkeley, CA. | |||

---- | ---- | ||

UC San Diego Soil Model: | UC San Diego Soil Model: | ||

{{UCSDSoilModelsMenu}} | {{UCSDSoilModelsMenu}} | ||

Revision as of 16:59, 23 September 2014

- Command_Manual

- Tcl Commands

- Modeling_Commands

- model

- uniaxialMaterial

- ndMaterial

- frictionModel

- section

- geometricTransf

- element

- node

- sp commands

- mp commands

- timeSeries

- pattern

- mass

- block commands

- region

- rayleigh

- Analysis Commands

- Output Commands

- Misc Commands

- DataBase Commands

PressureDependMultiYield material is an elastic-plastic material for simulating the essential response characteristics of pressure sensitive soil materials under general loading conditions. Such characteristics include dilatancy (shear-induced volume contraction or dilation) and non-flow liquefaction (cyclic mobility), typically exhibited in sands or silts during monotonic or cyclic loading.

When this material is employed in regular solid elements (e.g., FourNodeQuad, Brick), it simulates drained soil response. To simulate soil response under fully undrained condition, this material may be either embedded in a FluidSolidPorousMaterial, or used with one of the solid-fluid fully coupled elements (Four Node Quad u-p Element, Nine Four Node Quad u-p Element, Brick u-p Element, Twenty Eight Node Brick u-p Element) with very low permeability.

To simulate partially drained soil response, this material should be used with a solid-fluid fully coupled element with proper permeability values.

During the application of gravity load (and static loads if any), material behavior is linear elastic.

In the subsequent dynamic (fast) loading phase(s), the stress-strain response is elastic-plastic (see updateMaterialStage). Plasticity is formulated based on the multi-surface (nested surfaces) concept, with a non-associative flow rule to reproduce dilatancy effect. The yield surfaces are of the Drucker-Prager type.

OUTPUT INTERFACE:

The following information may be extracted for this material at a given integration point, using the OpenSees Element Recorder facility (McKenna and Fenves 2001)®: "stress", "strain", "backbone", or "tangent".

For 2D problems, the stress output follows this order: σxx, σyy, σzz, σxy, ηr, where ηr is the ratio between the shear (deviatoric) stress and peak shear strength at the current confinement (0<=ηr<=1.0). The strain output follows this order: εxx, εyy, γxy.

For 3D problems, the stress output follows this order: σxx, σyy, σzz, σxy, σyz, σzx, ηr, and the strain output follows this order: εxx, εyy, εzz, γxy, γyz, γzx.

The "backbone" option records (secant) shear modulus reduction curves at one or more given confinements. The specific recorder command is as follows:

recorder Element –ele $eleNum -file $fName -dT $deltaT material $GaussNum backbone $p1 <$p2 …>

where p1, p2, … are the confinements at which modulus reduction curves are recorded. In the output file, corresponding to each given confinement there are two columns: shear strain γ and secant modulus Gs. The number of rows equals the number of yield surfaces.

| nDMaterial PressureDependMultiYield $tag $nd $rho $refShearModul $refBulkModul $frictionAng $peakShearStra $refPress $pressDependCoe $PTAng $contrac $dilat1 $dilat2 $liquefac1 $liquefac2 $liquefac3 <$noYieldSurf=20 <$r1 $Gs1 …> $e=0.6 $cs1=0.9 $cs2=0.02 $cs3=0.7 $pa=101 <$c=0.3>> |

| $tag | A positive integer uniquely identifying the material among all nDMaterials. |

| $nd | Number of dimensions, 2 for plane-strain, and 3 for 3D analysis. |

| $rho | Saturated soil mass density. |

| $refShearModul (Gr) | Reference low-strain shear modulus, specified at a reference mean effective confining pressure refPress of p’r (see below). |

| $refBulkModul (Br) | Reference bulk modulus, specified at a reference mean effective confining pressure refPress of p’r (see below). |

| $frictionAng (Φ) | Friction angle at peak shear strength, in degrees. |

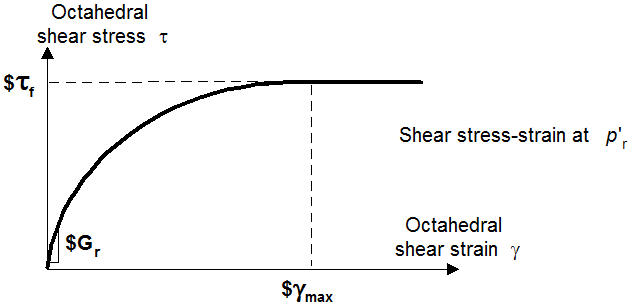

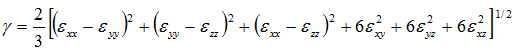

| $peakShearStra (γmax) | An octahedral shear strain at which the maximum shear strength is reached, specified at a reference mean effective confining pressure refPress of p’r (see below).

Octahedral shear strain is defined as: |

| $refPress (p’r) | Reference mean effective confining pressure at which Gr, Br, and γmax are defined. |

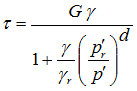

| $pressDependCoe (d) | A positive constant defining variations of G and B as a function of instantaneous effective confinement p’: |

| $PTAng (ΦPT) | Phase transformation angle, in degrees. |

| $contrac | A non-negative constant defining the rate of shear-induced volume decrease (contraction) or pore pressure buildup. A larger value corresponds to faster contraction rate. |

| $dilat1, $dilat2 | Non-negative constants defining the rate of shear-induced volume increase (dilation). Larger values correspond to stronger dilation rate. |

| $liquefac1, $liquefac2, $liquefac3 | Parameters controlling the mechanism of liquefaction-induced perfectly plastic shear strain accumulation, i.e., cyclic mobility. Set liquefac1 = 0 to deactivate this mechanism altogether. liquefac1 defines the effective confining pressure (e.g., 10 kPa in SI units or 1.45 psi in English units) below which the mechanism is in effect. Smaller values should be assigned to denser sands. Liquefac2 defines the maximum amount of perfectly plastic shear strain developed at zero effective confinement during each loading phase. Smaller values should be assigned to denser sands. Liquefac3 defines the maximum amount of biased perfectly plastic shear strain γb accumulated at each loading phase under biased shear loading conditions, as γb=liquefac2 x liquefac3. Typically, liquefac3 takes a value between 0.0 and 3.0. Smaller values should be assigned to denser sands. See the references listed at the end of this chapter for more information. |

| $noYieldSurf | Number of yield surfaces, optional (must be less than 40, default is 20). The surfaces are generated based on the hyperbolic relation defined in Note 2 below. |

| $r, $Gs | Instead of automatic surfaces generation (Note 2), you can define yield surfaces directly based on desired shear modulus reduction curve. To do so, add a minus sign in front of noYieldSurf, then provide noYieldSurf pairs of shear strain (γ) and modulus ratio (Gs) values. For example, to define 10 surfaces:

… -10γ1Gs1 … γ10Gs10 … See Note 3 below for some important notes. |

| $e | Initial void ratio, optional (default is 0.6). |

| $cs1, $cs2, $cs3, $pa | Parameters defining a straight critical-state line ec in e-p’ space.

If cs3=0,

else (Li and Wang, JGGE, 124(12)),

where pa is atmospheric pressure for normalization (typically 101 kPa in SI units, or 14.65 psi in English units). All four constants are optional (default values: cs1=0.9, cs2=0.02, cs3=0.7, pa =101 kPa). |

| $c | Numerical constant (default value = 0.3 kPa) |

NOTE:

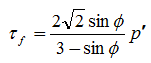

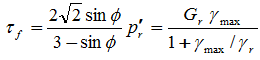

1. The friction angle Φ defines the variation of peak (octahedral) shear strength τf as a function of current effective confinement p’:

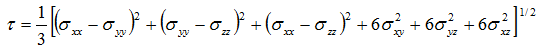

Octahedral shear stress is defined as:

2. (Automatic surface generation) At a constant confinement p’, the shear stress τ(octahedral) - shear strain γ (octahedral) nonlinearity is defined by a hyperbolic curve (backbone curve):

where γr satisfies the following equation at p’r:

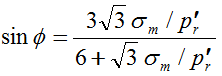

3. (User defined surfaces) The user specified friction angle Φ is ignored. Instead, Φ is defined as follows:

where σm is the product of the last modulus and strain pair in the modulus reduction curve. Therefore, it is important to adjust the backbone curve so as to render an appropriate Φ. If the resulting Φ is smaller than the phase transformation angle ΦPT, ΦPT is set equal to Φ. Also remember that improper modulus reduction curves can result in strain softening response (negative tangent shear modulus), which is not allowed in the current model formulation. Finally, note that the backbone curve varies with confinement, although the variations are small within commonly interested confinement ranges. Backbone curves at different confinements can be obtained using the OpenSees element recorder facility (see OUTPUT INTERFACE above).

4. The last five optional parameters are needed when critical-state response (flow liquefaction) is anticipated. Upon reaching the critical-state line, material dilatancy is set to zero.

5. SUGGESTED PARAMETER VALUES

For user convenience, a table is provided below as a quick reference for selecting parameter values. However, use of this table should be of great caution, and other information should be incorporated wherever possible.

| Loose Sand

(15%-35%) |

Medium Sand

(35%-65%) |

Medium-dense Sand

(65%-85%) |

Dense Sand

(85%-100%) | |

| rho | 1.7 ton/m3 or

1.59x10-4 (lbf)(s2)/in4 |

1.9 ton/m3 or

1.778x10-4 (lbf)(s2)/in4 |

2.0 ton/m3 or

1.872x10-4 (lbf)(s2)/in4 |

2.1 ton/m3 or

1.965x10-4 (lbf)(s2)/in4 |

| refShearModul

(at p’r=80 kPa or 11.6 psi) |

5.5x104 kPa or

7.977x103 psi |

7.5x104 kPa or

1.088x104 psi |

1.0x105 kPa or

1.45x104 psi |

1.3x105 kPa or

1.885x104 psi |

| refBulkModu

(at p’r=80 kPa or 11.6 psi) |

1.5x105 kPa or

2.176x104 psi |

2.0x105 kPa or

2.9x104 psi |

3.0x105 kPa or

4.351x104 psi |

3.9x105 kPa or

5.656x104 psi |

| frictionAng | 29 | 33 | 37 | 40 |

| peakShearStra

(at p’r=80 kPa or 11.6 psi) |

0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| refPress (p’r) | 80 kPa or

11.6 psi |

80 kPa or

11.6 psi |

80 kPa or

11.6 psi |

80 kPa or

11.6 psi |

| pressDependCoe | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| PTAng | 29 | 27 | 27 | 27 |

| contrac | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| dilat1 | 0. | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| dilat2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| liquefac1 | 10 kPa or

1.45 psi |

10 kPa or

1.45 psi |

5 kPa or

0.725 psi |

0 |

| liquefac2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0 |

| liquefac3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| e | 0.85 | 0.7 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

Pressure Dependent Material Examples:

| Material in elastic, drained (or dry) state | |

| Example 1 | Single quadrilateral element, subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 2 | Single quadrilateral element, subjected to monotonic pushover (English units version) |

| Material in drained (or dry), elastic-plastic state | |

| Example 3 | Single quadrilateral element, subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 4 | Single quadrilateral element (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 5 | Single quadrilateral element, subjected to monotonic pushover |

| Example 6 | Single 3D BbarBrick element, subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 7 | Single 3D BbarBrick element (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Material in saturated, undrained elastic-plastic state (coupled with FluidSolidPorous Material) | |

| Example 8 | Single quadrilateral element, subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 9 | Single quadrilateral element, subjected to monotonic pushover |

| Example 10 | Single quadrilateral element (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to msinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 11 | Single 3D BbarBrick element, subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 12 | Single 3D BbarBrick element (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Example 13 | A column of quadrilateral element (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Material in saturated, undrained elastic-plastic state (with user defined modulus reduction curve) | |

| Example 14 | A column of quadrilateral element (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

| Solid-Fluid fully coupled elements - quadUP element | |

| Example 15 | A column (2D plane strain quadUP element) of saturated, undrained Pressure Dependent material (inclined by 4 degrees), subjected to sinusoidal base shaking |

Code Developed by: UC San Diego (Dr. Zhaohui Yang):

References:

- “Numerical Analysis of Seismically Induced Deformations In Saturated Granular Soil Strata,” (1994), Ahmed M. Ragheb, PhD Thesis, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY.

- “Identification and Modeling of Earthquake Ground Response,” (1995), A. -W. Elgamal, M. Zeghal, and E. Parra, First International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, IS-TOKYO’95, Vol. 3, 1369-1406, Ishihara, K., Ed., Balkema, Tokyo, Japan, Nov. 14-16. (Invited Theme Lecture).

- “Prediction of Seismically-Induced Lateral Deformation During Soil Liquefaction,” (1995), T. Abdoun and A. -W. Elgamal, Eleventh African Regional Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, International Society for Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, Dec. 11-15.

- “Liquefaction of Reclaimed Island in Kobe, Japan,” (1996), A. -W. Elgamal, M. Zeghal, and E. Parra, Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 122, No. 1, 39-49, January.

- “Analyses and Modeling of Site Liquefaction Using Centrifuge Tests,” (1996), E. Parra, K. Adalier, A. -W. Elgamal, M. Zeghal, and A. Ragheb, Eleventh World Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Acapulco, Mexico, June 23-28.

- “Numerical Modeling of Liquefaction and Lateral Ground Deformation Including Cyclic Mobility and Dilation Response in Soil Systems,” (1996), Ender Parra, PhD Thesis, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY.

- “Identification and Modeling of Earthquake Ground Response II: Site Liquefaction,” (1996), M. Zeghal, A. -W. Elgamal, and E. Parra, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, Vol. 15, 523-547, Elsevier Science Ltd.

- “Soil Dilation and Shear Deformations During Liquefaction,” (1998a), A.-W. Elgamal, R. Dobry, E. Parra, and Z. Yang, , Proc. 4th Intl. Conf. on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering, S. Prakash, Ed., St. Louis, MO, March 8-15, pp1238-1259.

- “Liquefaction Constitutive Model,” (1998b), A.-W. Elgamal, E. Parra, Z. Yang, R. Dobry and M. Zeghal, Proc. Intl. Workshop on The Physics and Mechanics of Soil Liquefaction, Lade, P., Ed., Sept. 10-11, Baltimore, MD, Balkema.

- “Modeling of Liquefaction-Induced Shear Deformations,” (1999), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang, E. Parra and R. Dobry, Second International Conference on Earthquake Geotechnical Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 21-25 June, Balkema.

- “Numerical Modeling of Earthquake Site Response Including Dilation and Liquefaction,” (2000), Zhaohui Yang, PhD Thesis, Dept. of Civil Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, Columbia University, NY, New York.

- “Dynamic Soil Properties, Seismic Downhole Arrays and Applications in Practice,” (2001), A.-W. Elgamal, T. Lai, Z. Yang and L. He, 4th International Conference on Recent Advances in Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics, S. Prakash, Ed., San Diego, California, USA, March 26-31.

- “Computational Modeling of Cyclic Mobility and Post-Liquefaction Site Response,” (2002), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang and E. Parra, Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 22(4), 259-271.

- “Influence of Permeability on Liquefaction-Induced Shear Deformation,” (2002), Z. Yang and A. Elgamal, J. Engineering Mechanics, ASCE, 128(7), 720-729.

- “Numerical Analysis of Embankment Foundation Liquefaction Countermeasures,” (2002), A. Elgamal, E. Parra, Z. Yang, and K. Adalier, J. Earthquake Engineering, 6(4), 447-471.

- “Modeling of Cyclic Mobility in Saturated Cohesionless Soils,” (2003), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang, E. Parra and A. Ragheb, Int. J. Plasticity, 19, (6), 883-905.

- “Application of unconstrained optimization and sensitivity analysis to calibration of a soil constitutive model ,” (2003), Z. Yang and A. Elgamal, Int. J for Numerical and Analytical Methods in Geomechanics, 27 (15), 1255-1316.

- “Computational Model for Cyclic Mobility and Associated Shear Deformation,” (2003), Z. Yang, A. Elgamal and E. Parra, J. Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, ASCE, 129(12), 1119-1127.

- “A Web-based Platform for Live Internet Computation of Seismic Ground Response,” (2004), Z. Yang, J. Lu, and A. Elgamal, Advances in Engineering Software, 35, 249-259.

- “Earth Dams on Liquefiable Foundation: Numerical Prediction of Centrifuge Experiments,” (2004), Z. Yang, A. Elgamal, K. Adalier, and M. Sharp, J. Engineering Mechanics, ASCE, 130(10), 1168-1176.

- “Dynamic Response of Saturated Dense Sand in Laminated Centrifuge Container,” (2005), A. Elgamal, Z. Yang, T. Lai, B.L. Kutter, and D. Wilson, J. Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, ASCE, 131(5), 598-609.

- “Modeling Soil Liquefaction Hazards for Performance-Based Earthquake Engineering,” (2001), “S. Kramer, and A. Elgamal, Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research (PEER) Center Report No. 2001/13, Berkeley, CA.

UC San Diego Soil Model:

- NDMaterial Command

- UC San Diego soil models (Linear/Nonlinear, dry/drained/undrained soil response under general 2D/3D static/cyclic loading conditions (please visit UCSD for examples)

- UC San Diego Saturated Undrained soil

- Element Command

- UC San Diego u-p element (saturated soil)

- Related References